Dear Player: Uncharted Memories

“Have you got any pictures of these adventures?/ Well, I’ve got some great drawings!”

In Uncharted 4 Drake is notably more of a paper-pusher than in his previous adventures. By this I mean more than the by-the-books salvage job with which the game opens - throughout this adventure the player is invited to a have a keenly tactile relationship to artefacts. Intriguingly, like ‘The Order: 1886’ before it, this is a game which shows off its graphical innovation by getting the player to embrace a close relationship with paper, at a mechanical level, over more advanced documentary technologies. We scribble, and tear, and flip, and write and draw. We ‘remember,’ as both player and character, through the virtual pencil. Drake trusts in old media while he lies through his phone; the phone betrays our discoveries when we use it to take pictures, and Drake is by far at his most honest in his journal. So what does Uncharted 4 have to say about playing with technologies of memory, why does it elevate the act of drawing, and how is this reflected in the game’s other systems?

You just can't trust sat-nav these days.

There’s a lot of interesting memory work at the heart of Uncharted 4. When it comes to recording awe-inspiring landscapes, Uncharted has something interesting to say about the difference between taking a photograph and interpreting the world through a pencil. Central to this are the two principal means of remembrance in this game – Drake’s trusty journal and to a lesser extent it’s playful photo-mode both of which are invoked, I think, by the early conversation between Sam and Nathan Drake with which I opened this piece. In every Uncharted game, all is lost – fabulous adventures escape the lens, fantastic cities crumble, and all that remains are Drake’s notes and keepsakes.

This radical self-erasure fulfils some narrative ends, allowing the protagonist to remain permanently down on his luck, but it also helps establish a key theme: Drake’s life is a lesson in letting go of attachments, and none more so than in Uncharted 4. But what remains to the player? If Elena, the investigative journalist, never manages to acquire photographic evidence, what is the importance of paper, and perhaps more widely ‘touch’, as a ludic medium? From the outset of the series, Naughty Dog’s work has been compared to cinema, but over time I think the game has come to critique and nuance the photo-realism it is famed for. While its graphical work is spell-bindingly beautiful at the time of writing, it is the means by which we touch, mediate and let go of artefacts in the game through the controller that is both central to the games success, and its most innovative conceptual gambit.

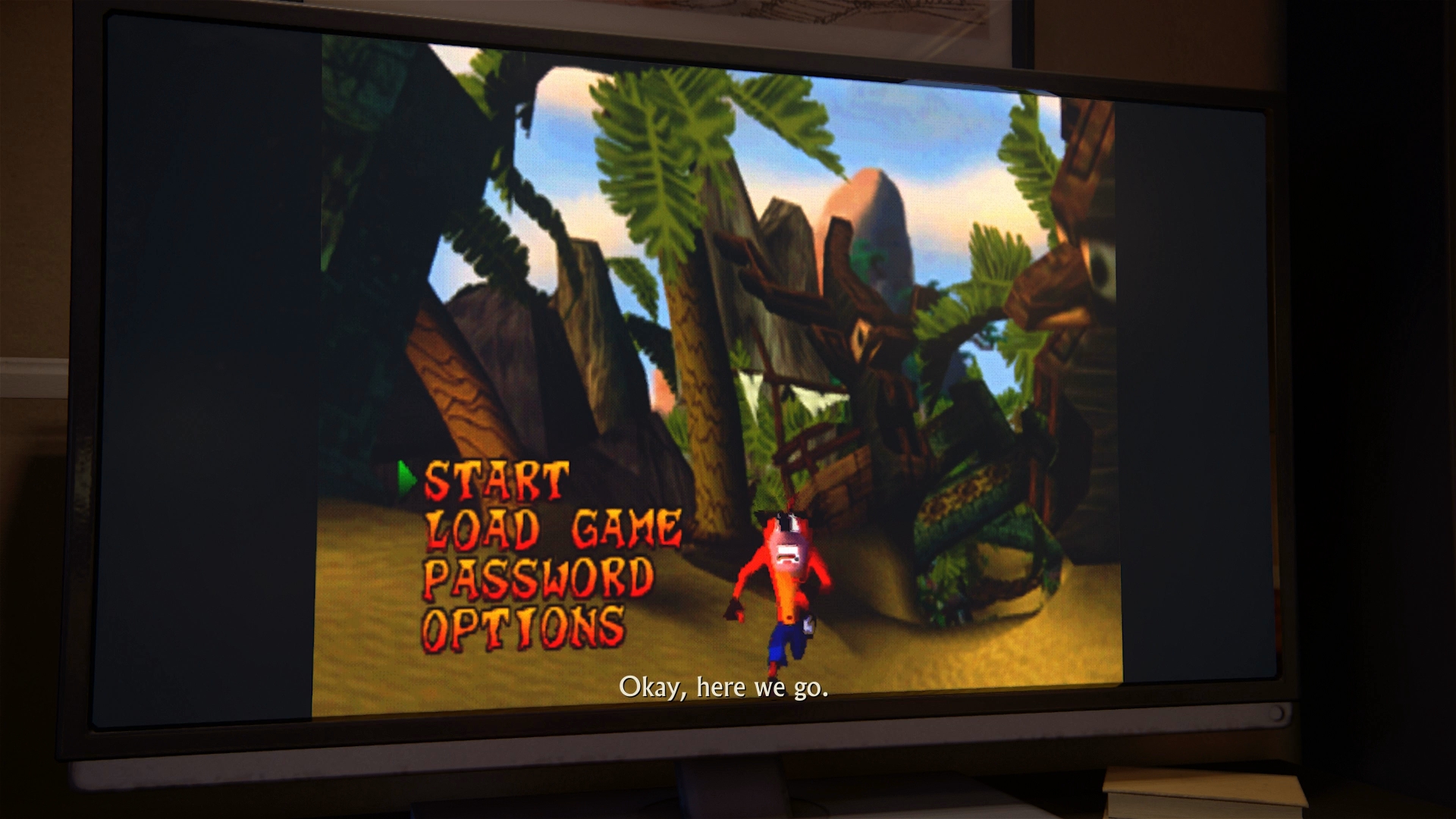

Crash, bless 'im, is also spell-bindingly beautiful at the time of writing.

Whether it be post-it notes left for his daughter, or the diaries of his mother, Drakes world is constructed through old media. A magnificent early scene returns to us in the epilogue, bracketing the game and demonstrating how one of the developer’s old PSX games brings people, generations, and audiences together by reflecting on the medium. We play Crash Bandicoot, we wait to allow the pretence of a disc spinning up and listen to the characters mock, joke and bond through the game. When Drake picks up that controller, we feel it in our own hands, and the profound human intimacy of play is given to us through an act of remembrance: Naughty Dog and Sony’s first venture into the third dimension. Moreover we first play Crash hot on the heels of an another act of fictive play and ludic touch – exploring our attic, picking over artefacts and memories of previous games before picking up a nerf gun to play fight with targets in the rafters. Here faux tutorial elements give us child-like curiosity – the world becomes strange and familiar at the same time. We appreciate games as the act of learning through iteration and adaptation, the kind of activity Jasper Juul argues keeps us coming back for more in his The Art of Failure. Uncharted is certainly self-aware, but the grace it carries itself with is also a subtle articulation of players’ collective memory – how games, like ancient artefacts, retain our memories.

Drake prototyping an in-game puzzle...

Drake’s journal is emblematic of this – from his witty cartoons of in-game events, to the storage of information key to our progress, this fictive diary reflects the game back at us. It records our progress as a strange and highly human index, a collage of pictures, text, narrative and problem-solving that mirrors the construction of memory. Unlike the cinematic narrative we experience in the present moment of the plot, the journal is an incomplete recollection. It is the arrangement and substitution of different mark making processes, scores and sketches, words which were thought but left unsaid, a mixture of connections and gaps, of fact and fantasy. Alongside the narrative, this journal has us flick back and forth through time – it’s a scrap-book and a to-do list, looking both forwards and backwards. As a tool it is both active and descriptive, conveying time (historical and personal) as a complex layering of different materials. Drake’s journal is a smooth intersection of possibility space and story-telling, guiding and reminding, and also allowing for the ineffable pursuits of the player and the hidden thoughts of the character.

When Drake tries to communicate with photography, his enemy intercepts his phone’s messages and location, only his journal remains useful and trustworthy. This journal is the space in which the interiority of the character unfolds. In the same pivotal scene, Drake uses its paper to create game counters, puzzle pieces with which to think through the permutations of a dead pirate’s machine. In Uncharted 4 we retro-engineer solutions using abstracted mechanics, creating the paper prototype of a problem originally designed by developers using similar means. The journal is a space of play and the record of play. The rough grain of its pages slides through Drake’s weather-worn fingers, as the character thumbs through pieces of the past, sometimes, personal, sometimes historical and sometimes showing his working – every page is a space for interpretive play with the game’s scenarios. As a dynamic object, the journal is “a real fixer-upper” as the captions of drake’s drawings often label the architecture around him. As a violent archaeologist, Drake is digging up the past, breaking it as much as recreating it. The world he lives in gives magical affordances to paper, iron and stone, all functional traces of old mechanisms – from the secret records of pirate kings to the sliding locks of a hidden staircase.

Thank god they splashed out on the memory card.

This is a deeply confident and playful game, nesting tutorials within tutorials within pastiches of tutorials. We even learn climbing and problem-solving using piratical machinery engineered to vet potential pirates in the fiction of the game. Drake’s interactions with the dead pirate Avery are all mediated through dead media – traps left for centuries, even mummies rigged to blow. We undeniably wreck the world we explore, but we also witness its last breath. By pulling and hooking and clambering and mantling we trace the environment and give it a moment of playful vitality. As we read the words of a letter, so too we read the surface of a wall, for points to grasp and play with. In Uncharted, textual memory meets experiential memory in ludo-narrative consonance. This is a game of rich textures and profoundly human surfaces collaged together in a master-stroke of ludo-narrativity. With a canny eye for the memories of its players, stretched across generations of games, it pokes fun at the photographic and cinematic while making every encounter with the media we’ve grown up with playful and memorable – be it a cathode-ray TV or an instant camera. In the photo-mode and unlockable filters we can see uncharted through a veil of ASCII, or cartoonish cell-shading, we can even remove the main characters from a shot and actively re-write our memories of the game. We play Crash, we play dress-up, and we play with the patinas of the past as we traverse a path well-trodden.

Tying, pulling, pushing, swinging, flipping, pressing, this is a game about feeling through time – a process of translation and transcription, between the analogue and the digital, the textual and the experiential, the camera and the pencil. Perhaps what Naughty Dog has best captured is the loving memory of a good game played, or indeed the way we remember through play. Drakes journal is a space of ludic memory as is the game as a whole. By the end of the game Drake and Elena haven’t let go of adventure, they’ve shared it, imbued it with new memories. Their daughter picks up Crash Bandicoot where her father left off.

Merlin Seller