Dear Player: Troubling Fungi and Desperation in The Last of Us Part II

What does it mean for a human to take on a fungus? In a rotting post-apocalypse, we can feel what it’s like to live a fungal life, to consume ourselves, to act in desperation ludically and narratively. Living beyond our time. There have been many contentious takes on this Summer’s biggest blockbuster, The Last of Us Part II (2020) – critiqued for having a laboured and dissonant moral rhetoric and for the problematic politics of its creative director; celebrated as a narrative of grief, depression and queerness; homophobically attacked for its representation of diversity as well as being legitimately challenged to handle queerness and race with greater nuance and depth. My reading here, however, follows Haraway’s (2016) injunction to ‘stay with the trouble.’ That life is messy, disturbing, and that that’s when it gets interesting. If this is a rotten game, wracked with shame and disgust and decay, I think we should treat it seriously as an account of living and dying well and poorly – both with our kind and with other species. If salient games are often lauded for their capacity to make audiences feel profound emotions like guilt, I argue that through traumatic repetition and ugly iteration LoU2expands ludic guilt beyond a simple revenge story and metastasises it into one of gaming’s richest and most intense ruminations on ‘ugly feelings’ (Ngai, 2005).

Donna Haraway and Sianne Ngai have different but related interests in messiness and ugliness. They both take issue with our inability to reckon with uncomfortable things, and with the rejection of dirt, they argue, we lose an appreciation of the subtlety of feelings needed to navigate a complex and often unpredictable world of limited agency. For Ngai this involves probing negative affects like envy and disgust to explore the ambivalences of modern life; for Haraway this is a recognition of our disturbing climatological times that doesn’t turn away from this trouble, but seeks to live with other lowly critters even in darkness, to become with worms, and viruses and fungi. In short, they invite us to stick our hands in the dirt, not our heads in the sand, and join what we find:

“[Critters] are not safe; they have no truck with ideologues; they belong to no one; they writhe and luxuriate in manifold forms and manifold names in all the airs, waters, and places of earth. They make and unmake; they are made and unmade. They are who are.” (Haraway, 2016: 2)

My interest in LoU2 is in the affective trouble of Abby and Ellie’s narratives, and the non-human life that subtends them. In Botany, to subtend is to stand close to, to extend under, to support or enfold, and the world of LoU2, subtending the characters, is a green-brown palette of flora and fungi. Every character conflict is enfolded by a non-human conflict that spreads across the ruins of humanity – animal life is eclipsed by the plants that break and envelope the architecture of sentient apes, and parasitic mushrooms that devour every ‘body’ in sight. This isn’t your average zombie story – the entire ecology seems to have changed following the fungal outbreak, and while humanity consumes itself, plants and fungi have been busy consuming whole skyscrapers. What it means to be human in a time when humanity is irrelevant is a question that haunts every character, one which is read by the player in very inhuman terms of growth and decay as the apex predator of the old world becomes a detritivore of the new. When Owen says that Abby and company have lost their humanity because they ‘stopped looking for the light,’ it’s a tacky refrain but it’s also a reflection of our biases towards the enfolding theme of photophilic plants and photophobic fungus. The tragic fact is though, in this flora-fungi war, we don’t have much of a choice in what we look for.

The linear narrative is deeply determined to show us, through lines of guilt, desperation and exhaustion, that we barely have space to breathe, let alone think. Like the choked corridors of fungal spores, this world is tight and anxious. We kill, and kill and kill, and there are no grand decisions, just the rhythm of desperate combat rolling from crisis to crisis and bottle to brick. So much of LoU2’s captivation motion-capture focuses on breath – dragging air into our lungs between existential threats and unconscionable acts. As the player turns from Ellie’s decent into depressive vengeance to Abby’s struggle for kinship, we are made deeply aware of the similarities in their tales, their childhoods, their loves, the murderous wildness of humans in troubled times. The daring turn from one to the other reveals the dizzying depths of guilt and pain in this world – giving us another perspective also entrains a vast multitude of perspectives. NPCs grieve – guards barking the names of the countless people we kill. Every minute is a new tragedy, implying further invisible tales of desperation beyond the screen. By pluralising perspectives, we can start to even dig beyond humanity in the context of flora and fungi. After all, everything in this world is soaked by the same rain.

Ancient 8m tall Prototaxites

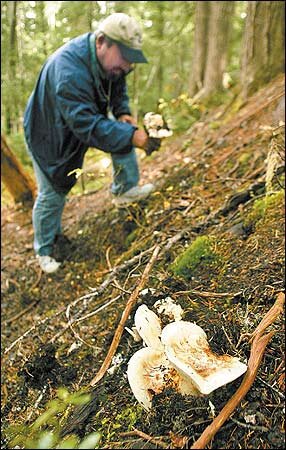

Matsutake near Seattle

This new ecology is indeed nothing new – plants and fungus once fought for domination of the land before the Carboniferous, ancient fungi even growing metres tall, and ever since then the biomass of the plants above the soil and the fungi beneath have dwarfed those of the animal kingdom. Humanity has always been food for mould and moss, critters we barely treat as if they were alive - and this terrifies us, as Dawn Keetley and Angela Tenga explore in their analyses of plant horror (2016). Closer to our time, and the geography of TLoU2, Anna Tsing (2015) explores how the rainy U.S. pacific northwest became the centre of an international trade in fungus – the prized matsutake mushroom. This is a mushroom that can only grow in post-industrial ruins, a mushroom that famously grew even in the wake of Hiroshima, and needs old woodland to be felled and replaced with pine monoculture in order to flourish. The old timber industry of Oregon and Washington state, now collapsed, have proven a productive mulch for mushrooms to grow in troubled times, and in thinking through their patchiness and their complex gatherings of surviving critters, Tsing sees mushrooms as an imaginative bridge for us to explore how “places can be lively despite announcements of their death… In a global state of precarity, we don’t have choices other than looking for life in this ruin.” (2015: 15).

And so following Tsing’s book, The Mushroom at the End of the World into Seattle, we find the player of TLoU2looking for life in the ruins, surrounded by fungal stories of flourishing that dwarf our human dramas but also recompose and compost them with the Cordyceps fungus. The existential questions that harrow Ellie are ones we already have to deal with in our present troubled times – our deaths don’t mean much, in the grand scheme of non-human things, and so the question of what we do with our lives is fraught. The choice isn’t simple, between growth and decay, both are needed, both will always happen, but there are better and worse ways of getting our hands dirty. Whether as a player we have a choice about it, however, is another matter.

Our protagonist, Ellie, is trapped in an unhealthy circuit, a dying ouroboros of finite self-consumption. And we are pushed through it again and again. I argue that to spurn LoU2 as a simple tale of the short-sightedness of revenge, the same guilt trick performed on us since Spec Ops: The Line (2012), is to miss the subtlety of LoU2’s affects. As Ngai argues, we’d rather look away. LoU2, however, forces us to sit with precariousness, disgust, shame, ignorance, trauma, masochism, anxiety and depression for 30 hours. Like many others, I put down the controller many times, praying I didn’t have to keep inflicting pain, but finding that, with narrative inevitability, I had to. It’s uncomfortable, it’s troubling, but it’s more than one shade of guilt: the guilt of callous action, the guilt of not forgiving, the guilt of failing who we love, the guilt of not being able to forget, the guilt of surviving when others don’t. It’s only in retrospect that we understand Ellie’s compulsion.

LoU2 has us begin with a unique narrative hook – the protagonist’s motivation is a lie: we know the truth behind a lie, and Ellie knows it too. When we lose Joel, we know he’s dirt – an asshole who doomed humanity - and at multiple junctures, Ellie’s question for vengeance ‘for’ Joel is far from passionate. Instead, as Noah Caldwell-Gervais argues, Ellie keeps going because – in the grips of deep depression – she can’t see beyond it. This depression isn’t precipitated by a recent crisis, but goes back years, to her realisation that she is immune, and later to the fact that if Joel had let her be sacrificed, humanity would have the cure. In her last conversation with Joel, as we finally hear it, Ellie confesses her real motive: “I was supposed to die in the hospital. My life would have fucking mattered.” In LoU2, Ellie goes back again and again to death and destruction because in a world where she is alive nothing matters. Fittingly, tragically, this is a world where she cannot die – nothing is strong enough to kill her, and she is fated to persist, to live beyond her time. In the final, shameful confrontation, Ellie has followed Abby to the ends of the world because only Abby might be strong enough to end her, to give some kind of meaningful closure to a life that has been suspended for years, to give closure.

“Take on me (take on me)

Take me on (take on me)

I'll be gone

In a day or two”

But crumpled on the beach, she knows that nothing can take her on. She is the player avatar, badass and checkpoint-saved, and no player can truly die. They can only suffer. In this game, we can’t escape the trouble and the shame. We live with finitude, wishing we were already dead, shedding pieces, like a fungus that can only live within the means of the decaying body it finds itself on. This is perhaps an especially bleak form of Lauren Berlant’s idea of slow death – the all-too-familiar condition of being worn out, precarious and focused on the “ordinary work of living on” (2011: 761). From the perspective of Abby's anxiety, we live in vertigo - both a fear of heights and our desire to fall. The quick button prompts to grab and through objects in desperation acting out the work of maintenance in a condition of slow death. Perhaps that's what LoU2 knows will keep us playing? Ugly affects before and behind the screen compel us, and they are communicated as much by non-verbal cues and subtext as text. The richness of motion-capture that can hold our collective breath can also differentiate between honesty and dishonesty, passion and awkwardness, meaningful glances and haunted forbearance. We see the cost of “living on” in our exertions.

This motion capture mixes with the kinds of vegetal and fungal growth we only see in hindsight, by its traces and the body it consumes. The trouble draws bodies together, and we see this clearly in both the collaboration of Abby and Lev, and the Rat King Abby faces. The fungus’ capacity to animate and conjoin limbs, to take on people, echoes Ellie’s consumption of herself and everything she cares about. Abby, however, finds something different in the humus - she finds kinship with lev and escapes the cycle of generational, 'sins of the father,' guilt by opposing it with a queer non-reproductive family that rejects that history. But Ellie's queer family is haunted by ‘the light in the shade of the morning sun,’ to quote famous lyrics from the game’s trailer. We don’t know if we’ll be gone in a day or two, but we find ourselves both locked into the chrononormativity (Ruberg, 2019) of our new family and the inescapable trauma and guilt which undoes it as we leave our new home in search of closure.

In the end Ellie is motivated by survivor's guilt, not the loss of Joel, Joel represents the last shred of human, narrative meaning for life in the horrible purgatory he condemned her to. We see it in Ellie’s 90s nostalgia, her feeling 'after her time' – first nostalgically as a kid in a museum and then melancholically as an adult with a white picket fence. We even see it in the emotional vertigo Ellie faces in feats of disgust and anger that push her deeper and deeper as she grows smaller and smaller. The affective deadlock that TLoU2 faces us with is the subject position of a tragically suicidal character that doesn’t want revenge, but wants to have died when her death meant something. Yet whatever mortal peril she immerses herself in, she can’t die. Being both immune and indomitable she can never meet her match – death eludes her. Perhaps she is a fundamentally cursed to be an avatar curiously aware of her fate, doomed to kill and never be killed. Or perhaps Ellie faces the player with two kinds of death – the slow death of alienated, vengeful struggle versus death from the point of view of the fungus, decay as a new beginning.

The darkest part of the TLoU2 is the realisation that Ellie is stuck like the inert fungus in her head, unable to bloom and become part of the wider ecology. Stuck in the liminal ruins of the old world, she and Abby are two examples of the kind of trouble that survives – two different kinds of fungus, one a powerful, progressive flourishing of bodies, the other a tragic kind rot, locked in its own skull. We can identify with both, but what takes time and repetition for a player like me to appreciate, is that immunity in this world isn’t actually an ‘advantage,’ but rather a curse – to be alienated from others, human and non-human alike, unable to compost with kin.

As Ellie strums her guitar in the final scene, and having lost two of her fingers she can’t complete a chord. She is gone, but from every ruin comes the potential of new growth, even if it takes ‘a day or two.’ In spite of all we’ve done, plants and fungus continue: “they are who are” (Haraway, 2016: 2). And in spite of all its ugly affects, The Last of us Part II gives us interesting trouble to think with.

Dr Merlin Seller

Lecturer in Design and Screen Cultures

The University of Edinburgh

Bibliography:

Berlant, L., 2011. Cruel Optimism, Duke University Press.

Haraway, D.J., 2016. Staying with the Trouble, North Carolina: Duke University Press.

Keetley, D., Tenga, A. & SpringerLink, 2016. Plant Horror Approaches to the Monstrous Vegetal in Fiction and Film. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ngai, S., 2005. Ugly Feelings, Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Tsing, A.L., 2015. The Mushroom at the End of the World, Princeton: Princeton University Press.