Dear Player: Mad Max and Theseus' Ship

‘A sailing ship?’ Asks disdainful Chumbucket (engineer, age unknown), ‘heretics messing with natural forces is sacrilegious, the Archangel Combustion is the only Way!’ As I watch Pink Eye’s land-ship sail out into the Great Nothing, I wonder if they were the lucky ones. Or whether their death is as certain as the world’s. This is the Dead Barrens of Mad Max – a world recycled, perturbed, lost and found. The player stands at the edge of a game world well aware of its limits. I turn and I jump back into the centrepiece of the game, a bricolage of scrap, pistons and oil all grinding against each other in an effort to become a car called the Magnum Opus. This is a car that wants to make the same journey – beyond the expanse of nothing. Sure it’s a shiny ark, but I’m not entirely sure what I’m trying to save. The car has technically got more personality than either the protagonist or the damsel-in-distress trope could ever muster, but it provides little stability for the player. This is an atmospheric game, but it’s also one that lacks ‘character’, ‘originality’, or ‘authenticity’ on multiple levels. Mad Max is a post-modern game in every dimension. It borrows unashamedly from AAA games left right and centre – Arkham, Tomb Raider, Just Cause, Assassins Creed, Uncharted, Burnout, the list goes on. In fact, it’s nearly infinite – everything in this game is recycled, thematically and structurally. Max drives a bundle of scrap. He feeds her and upgrades her, and piece by reclaimed piece the player makes a glorious ride. Max just wants to fill a car-shaped hole in his heart and get the hell out of dodge, but the world they have to survive together makes for an epic odyssey. Mad Max poses interesting questions about both the development ‘of’ games, and development ‘within’ them: What is character development when your car has more personality and raison d’etre than you do? What does it mean to progress in games? What makes a game ‘original’?

Like Shadow of Mordor, this game is a finely tuned amalgam of successful precedents. It stands on the shoulders of many giants, but its lack of originality has led to mixed reviews. Understandably, some see a movie-franchise game like this to be yet more evidence of a risk-averse industry re-treading well-worn ground. Even Martin Robinson’s positive Eurogamer review ends on a note of repetition: “You'll have played other, better examples of the genre, and you've likely been a tourist to the post-apocalypse a few too many times before, yet Avalanche wears the fiction so well it's hard not to be charmed by this brutal, beautiful open world.”

We live in interesting times – the end of everything is now the beginning of so many stories. But perhaps tellingly, it’s not clear how Mad Max’s world died. Sure there are hints, and a wonderful array of historical artefacts Max has a comically bleak exposition of, but there’s no smoking gun. If anything, it seems to have been a combination of factors – global warming (‘the big wet’), nuclear war (or at least something sufficient to level cities in one or two decades), and inexplicable drought. That’s a biblical litany of plagues right there, but it’s not complete. Indeed one of the most interesting qualities inspired here by the films is the titular ‘madness’. Were people broken by the collapse of the world, or was it madness which brought us to this point? As ‘Fury Road’ asks of itself: “who killed the world?” – was it us? Does it matter? Have we lost guilt with the end of everything else?

Our protagonist suffers from amnesia, but through introspection he only learns how to become a better nomad. His mono-mania is escape, to move on, to never stop. In this he mirrors player aspirations – we upgrade, we progress, we unlock, all for the sake of further progress. We look out at the edge of the gameworld – the endless flat ‘Plains of Silence’ – and we wish to cross it, to drive our character out of the game itself, to become something more. But he never will. This is a game well aware of its limits, as well as its potential limitlessness. It is a game which concerns scarcity, but which offers abundance – it’s oil respawns, it’s scavenged scrap becomes a growing income.

The apocalypse is productive destruction, something old becoming new, and while the world might have to die, but only to weld an infinite number new ‘post’ worlds together. Mad Max is mechanically akin to its thematic ‘origins’ – it is fractured, multiplied, all the disasters and horrors of all the disaster movies and horror games. We have been tourists of the post-apocalypse before, that is true, but we can never step in the same river twice. The Great White is a hybrid world, perhaps even a sattirical take on previous Armageddons – everything that could happen did happen. The world, we could say, is made from successful un-makings – unravelled narratives are the base unit of this open game. It is a mad cacophony, but also a beautiful example of the carnivalesque. It’s a bit like Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture, but some new folk turned up to have a party.

The world is upside-down – seas are deserts, fossil fuels are everywhere, the enemy even seems to come back from the dead. The game is, not unsurprisingly, like a game: both infinite and finite, immersive and unreal. Our missions repeat the same basic rules, but with huge variety. When we help wastlanders we often have to fetch something lost, but only ever to make it something new – a tarp turned sail, a crab-shop sign turned religious icon, fairy-lights turned into mass spectacle. We return and repurpose fragments of the old world in the same manner that our car grows old, sheds its components and acquires new ones.

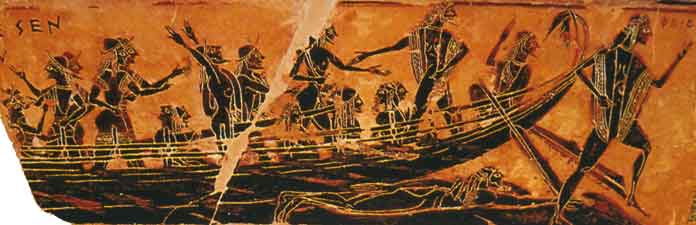

I am reminded, in the end, of a conundrum, a thought experiment called ‘Theseus Ship’. We’ve all heard various versions of it, and none of us have answers, but as our Max loses everything yet persists, and our car retains its name but changes all its parts, we’re given some questions. Imagine a ship, a famous ship, in this case the one that made the famous Greek Odyssey in search of home, identity and immortality. Now imagine a part breaks and gets replaced, again and again and again. Eventually not a single original part remains – is it still Theseus’ ship? At what point does it become something else? But wait, there’s more. Imagine that simultaneously each broken piece of Theseus’ ship is put back together in shape of the original, with all the original materials, but a new construction? Now which is Theseus’ ship? What the heck happens to the idea of the ‘original’ or ‘authentic’ at the half-way point? Is suppose I have to say the answer is whatever ‘floats your boat’.

Mad Max may lack ‘originality’, but it makes us question what that even means. Every game is staked in repetition, in tradition, in languages made familiar to the player through previous games or preceding tutorials. Mad Max’s car is in a constant state of becoming, just like the game at large – each new component adds at the same time as it overwrites. The wasteland is the accumulation of the mechanical successes of other games, but is also thematically the other ship – the accretion of everything lost in previous apocalypses.

What seems like a loss of agency and identity to some is an epic party to others. The world churns and we’re along for the ride. In life as in-game, there is no original, no persistent identity to things, only sets of shifting contexts. Which ship is Theseus’s? Either one, neither one, what matters if that weird one made from all the broken parts actually floats. Like the Magnum Opus itself, this great work is a game of many circulating parts, and boy does that engine purr.

Merlin Seller