Dear Player: Everybody’s Gone to the Uncanny Valley

The lush golden haze of Yaughton is quiet, but far from peaceful. Fictional places are weird things, they make space where formerly there was none, but they can feel like they’ve always existed. The never-was is hard to erase. The Archers reside in a county planted between two real counties, a piece of Little England that never existed, but has been ‘around’ for over half a century. The Radio 4 show is emblematic of continuity, preservation, conservatism with a small ‘c’ – characters last, and when an Archer dies, they pass the farm on to the next. No-one just ‘disappears’. Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture, poses exactly this crisis. What happens when an imagined community ceases to be? What if you got to heaven and it was empty? An engrossing and tantilising Mary Celeste, these fictional Shropshire villages from the makers of Dear Esther are lost in time and space. There former inhabitants are just disembodied voices – motes of light. We see nothing but traces of what was – from blood-soaked tissues to signs of ‘aliens’ attempting to communicate. By the end we see both are one and the same.

Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture is so powerfully rich and multi-facetted that no single text could ever convey the whole experience. I could wax lyrical about the beautiful soundscape, or the brilliant simulation of British weather. The moving human relationships explore loss, acceptance, love and misunderstanding in a way that elegantly reflects and extends the motif of alien contact, and vice versa, and it cannily and subtly balances the variety of human response in exposure to complete alterity. What I want to do here is reflect on what this game can tell us about ‘play’, and what it can mean to inhabit someone else’s world. I’ll be prone to hyperbolic analogies, but if you bear with me, we might explore some of the more interesting paradoxes of simulation, and the joys of losing ourselves in a game.

A first-person experience, an elegantly paced mystery, this game lets the player read and listen to artefacts of the recent past. Conversations, opaque codes, self-reflective radio messages are all left for our roving perspective to engage with or ignore at our leisure. We intrude, always, in the middle of something – from theoretical physics, to doctor’s visits, deaths and transitions. The beautifully realised world copies everything from the dust of its interiors to the waxing and waning sunlight of its mesmerising landscapes with beautiful photographic detail. Like the Vanishing of Ethan Carter, photogrammetry has captured and transposed real-world textures to lend Little England a concreteness which seems all the more hauntingly real for its lack of occupants.

It’s worth noting that photogrammetry doesn’t work nearly as convincingly for animate objects, for moving bodies. While CGI can convincingly replicate objects in movies, it still struggles with the impression of ‘weight’, something which becomes obvious when a body moves. We’ve all witnessed the slow ballet of character animations, the ‘floaty’ quality in everything from Chappie to Killzone, which even besets those which are motion-captured. The Vanishing of Ethan Carter, like Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture, is centred on a search for missing persons in an uninhabited environment, and the design choices of the game-world and its mechanics coincide perfectly with the current limitations of graphics technology.

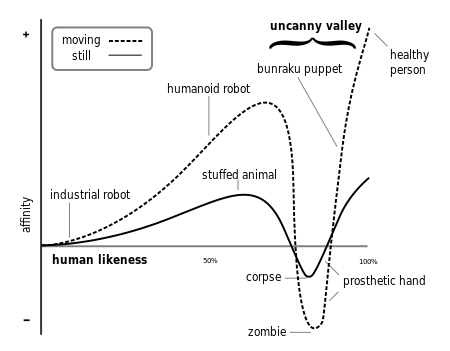

This may look suspicious, and we may be inclined to take this as a reductive ‘explanation’ of the game - the idea that these scenic melancholy masterpieces are empty from technical necessity. Every Body HAD to go to the rapture, or else the illusion of reality would be ruined. But this itself is significant. Limits make games, and games have to be aware of their limits to succeed. In EGTTR we find technical limits taking us to interesting philosophical places – its design choices mesh graphics with narrative. La nature mort, still life, is beautiful, and often the focus of intense mimesis, but its unchanging details betray its nature as a fixed image. As a representation increasingly approximates what it represents, we begin to notice more of what’s left out than of the successes achieved. A good caricature can be more successful than something creepily close to the real thing.

The ‘uncanny valley’ is a name for this phenomenon – a trough in positive responses to an increasing tendency towards naturalism. Just before something looks real, it looks super freaky. Ever been scared of a doll, or seen a movie about androids? You’ll know what I’m talking about. When something’s almost right, but not quite, we experience the Uncanny. The realism of games like Ethan Carter and EGTTR is based on a very unreal contrivance – ghost towns, it turns out, are the closest we get to living breathing ones, but there’s something melancholy about this. Still-born, even at the cutting-edge, games fall short of reality. The genius of EGTTR is that it makes a strength of what it lacks

We can lose ourselves in the The Archers because we’ve never been to ‘Borsetshire’. We can’t get close enough to see the imperfections that tell the lie. In disembodied voices we trust. Illusion at its best, is hidden right underneath our noses and the uncanny can be the most affective of tools. In his history of noise, Prof David Hendy shows us how powerful the disembodied voice can be. When radio was being developed as a mass medium, it had the power to persuade its audiences in a way no other had. Both the NSDAP and the BBC made use of the fact that a voice without a body could speak with persuasive immediacy, it could be both public and personal, it could get inside our heads in a way that a physical speaker could not. Almost hyperreal, a radio voice is more convincing because there’s no-one there to convince us but ourselves. It gets close to our own inner monologue, approximates thought. People, even real people, are imperfect, but voices are like the soul after death. In EGTTR we lose ourselves in its community because of, rather than inspite of, the fact that nobody is there. Like with the radio, we let the voices in, but unlike The Archers, we know these are ghosts. We know these people never existed, and their absence is all the more provocative for it.

The game is set in the 80s, but it doesn’t look at historical vanishing communities or existential threats – mining towns drying up, cold war architecture – but instead at Thatcher’s 'heartland'. This might seem bizarrely conservative, even ironic, given that Little rural England was a myth forged alongside the birth of radio, a self-satisfying imperial fiction with which countless Conservatives have elided our conquests, and stirred fears over immigration. But Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture looks at the myth of Little England, and guts it. In the course of our exploration we learn that the area is being destroyed by an external influence, one that came as light into the observatory, and which threatens to spread through the phone lines as yet more electromagnetic energy. The military’s solution is to isolate it until it disappears, and even one of its main characters call for their own eradication to spare the rest of the world. The toxic myth of plucky Little England deconstructs itself in magic-realist style. It brings together The Archers and The X-Files in an explosion of light. The place that never was fades away, an imagined community destroyed, and the Player sees the melancholy bones it leaves behind.

But this game also asks us questions about ourselves, and about the nature of games. EGTTR uses a deeply unreal and uncanny event to convey one of the most convincing and moving impressions of a community in gaming history. There may be no bodies, but the traces left behind are made all the more ‘real’. Disembodied voices, in a fictional non-place, weave us into a game narrative with a pensive approach to space. We cannot change what has happened, we can move no objects, but this game gives us an immense awareness of time and loss. We feel deeply ‘in world’. As we move, time moves differently. On entering a village, or encountering a ghostly conversation, the sun moves in the sky, accelerating time backwards or forwards to the extent we know as much about ‘when’ we are as we can place Yaughton on a real map. Shadows lengthen and rotate around us, we string together time in loops and bunches. We feel time moving around us, rather than feeling the world move through time. Everything is static, locked in a yester-year, but yet we warp through it, the sun our only witness. As we replay memories and marvel at the concrete detail of an impossible situation, we are confronted with the uncanny.

If everybody’s gone to the rapture, where are you? Many players feel the ‘open’ world of this game gives us a deeper attachment and greater agency in the world, but we touch nothing, and we walk in a circuit. The map is a circle, which, like EGTTR’s peripatetic sun we stumble around, back and forth, but never outwith its orbit. Restricted to a slow pace, this game is open about the fact that it controls us rather than the other way around. No-one ‘inhabits’ the game, the game’s code merely ‘runs’ us, moving around the Player like a river around a stone. We approach this world as if an alien from a different dimension, and is that not what we are? We sit still at our console while the virtual world passes us by. We are no more ‘in’ this world than Yaughton is in England. If I could chance one more analogy, we are not given a message in bottle, but rather are asked to cast ourselves into the sea.

Like the alien ‘pattern’, we lose ourselves in the encounter with this magical game, the player is figured not as a controlling protagonist, but an exploratory bundle of experiences. Like the pattern of alien light, we are aliens playing in a different world, physical humans roaming a virtual space. Much as the ‘pattern’ imprints and inflects the world, causing unintended pain and misunderstanding as it explores its environment, the player learns what it is like to live on an alien world, and thinks deeply on the problems of overcoming difference. To activate a ghostly memory, the player is even asked to move the controller in three dimensions. We spin the controller as a whole until it vibrates in resonance with the pattern of light – we are taken physically out of the game, made aware of the interface, and consider ourselves as part of the flux. We reflect critically on what it means to be part of an imagined community in existential crisis.

In many ways, this is what it is like to play a game. We do not ‘read’ this hypertextual narrative, space and time in the interactive medium treat us to something entirely different, we ‘harmonise’ with narrative, we feel its affect while losing ourselves. Most games might try and immerse us in a story by getting us to live through the eyes of its protagonist, to ‘perform’ the narrative. Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture is powerful because we aren’t there, and we never can be. We feel intensely lifted from our bodies. There and not there, the same but different, playing games can take us to the Uncanny Valley. What Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture offers us is a chance to feel as de-realised as this non-place. We don’t walk through this game, instead the game intersects with us. We are the lens which brings its light in and out of focus as we tilt our controller to squint at that which never was.

Merlin Seller