Dear Player: Scanning Time

It's like Plato's cave... without a happy ending.

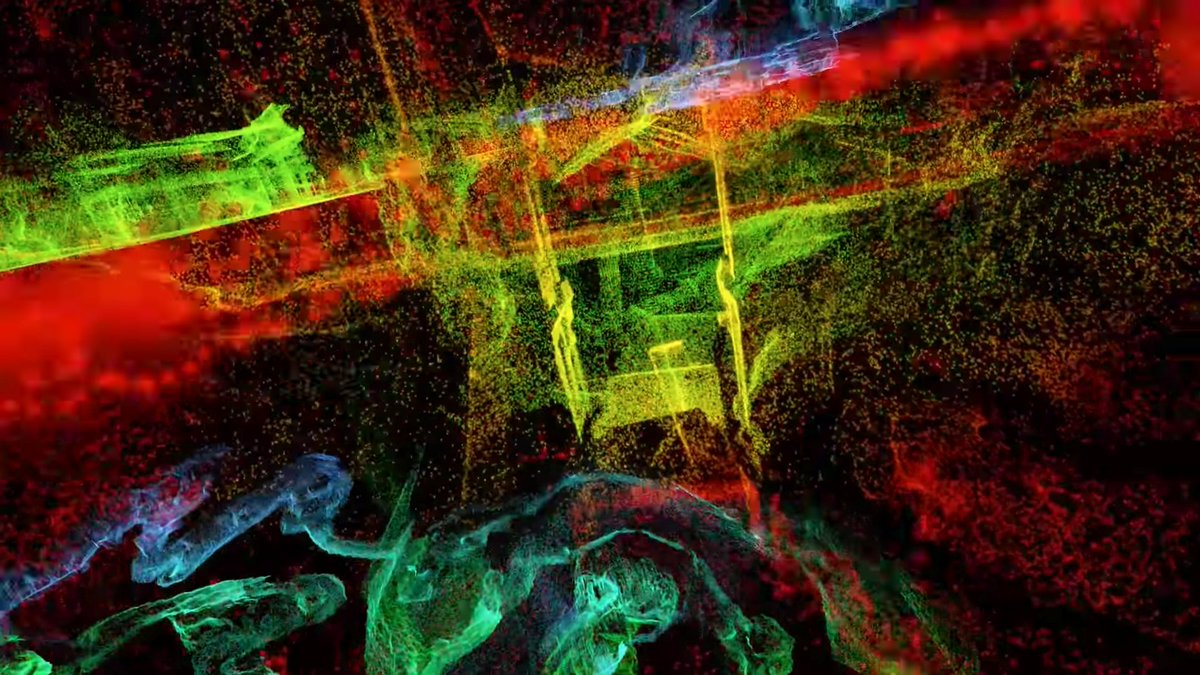

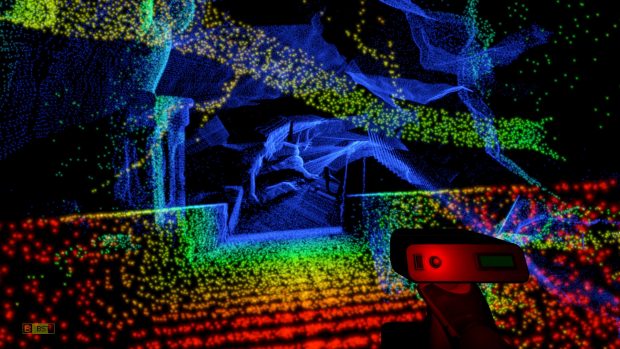

Scanner Sombre does what games do best, it gives us a disarmingly intuitive tool with which to question our intuitions about the world. This is a game all about the act of archaeology - feeling out a space, sifting through shadows and peeling back traces with blind but methodical rigour. Equipped with a LIDAR scanner we bounce dots of light off the objects around us until we begin to perceive shapes in the pointillist confusion. We paint the world around us like a street artist, and the more colourful light we spray onto the walls the higher fidelity they appear. As we uncover a dark palimpsest of histories and experience glitches in the scanner, our perspective and our memory of space becomes increasingly disjointed. Introversion's Scanner Sombre lets us experience a world at a remove, and thus allows us to reflect on time and sense perception

“What we experience in this game might be described as a world without a fourth dimension.”

A short and incisive low-challenge experience, it joins indie titles such as Unfinished Swan in presenting something akin to a walking sim, but with a focus on providing meaning through experimental mechanics rather than environmental story-telling. True, there is a narrative here, but it acts as a hook for larger questions about being and knowing in a cave filled with digital ghosts. At a (literal) textual level, the narrative of Scanner Sombre is a kind of melancholy diary we've seen before, stringing together disparate clichés, but it serves as an index of time - both relative to the player character and the iterative tragedies of this cave system. This place was home to ancient cults, early-modern witch-hunters and industrial mining accidents. The core takeaway here is that this environment is one of serial loss, a land of traces and metonyms then and now, footsteps and scans and statues and mannequins. Story is a scaffolding for ideas. Like the fit-for purpose UI and the rigid scanning device in our hand, all aspects of this game are practical and unobtrusive in the service of directing our attention to the process of scanning itself.

I suggest there is now a distinct and more conceptual than narrative tradition of walking sims.

The simplicity of the scanning process itself belies a conceptual complexity. The player must constantly judge whether they 'know' what lies before them, what level of information is enough, what level is excessive, and whether these dots tell them more about the scanned or the scanner. Sensing an environment is piecemeal, cumulative, and comes with the potential for obsolescence, where a statue may move since you last scanned it, leaving a hollow shell indistinguishable from the rest of your scanned topography. You don't know what you're missing in Scanner Sombre, and you don't know what you can rely on from what remains. The game feigns transparency at first, and indeed offers extensions to your sensorium as well as restrictions - you can see through walls to areas you have already scanned, and you later unlock the ability to scan in sweeps and distinguish metal from rock. However, these affordances cannot sate the player's inner sceptic, and cannot live up to the naturalism implied by the game's subtle soundscape. when we initiate a 360 scan around ourselves, the striated rows of lasers cover a lot of ground, but they toy with our sense of space. As an expanding sphere of laser-lines, they make all surfaces appear concave from a fixed point until we move around and build up a stereoscopic frame of reference, as if we are painting a tromp l'oiel onto the cave walls. The player seems to be living in a virtual world behind which lies the real thing. In sensing the world we paint over it.

Muybridge's chrono-photography

Colour in this world is a spectrum that only connotes proximity - living, dead, ghostly and physical everything is effectively monochrome. Beds and torture devices are made of the same visual stuff, and read as equally banal and concrete. The player can only speculate on the blood-stained graffiti that goes unseen. We can only mark and note the presence of a hard surface. Water eludes us and movement can only appear as a fleeting instance. Unlike a conventional walking sim, a room doesn't reveal itself to us all at once as an image when we turn on a light switch, instead we have to touch every object with our scanner. When figures start to emerge from the murk there is the implication here of a kind of chrono-photographic procedure in the way we document the world - like some ghostly post-digital Muybridge - but these traces can vanish and move, further confusing our sense of time and space. Like chrono-photography, there is a sense of time and detail lost - we can break down the world into dots, but our resolution is never high enough, like the way in which proto-film lacks the number of frames to fully capture its subject or (in a Zeno's-paradox-kinda-way) the passing of time. In a manner reminiscent of the Angels in Doctor Who, our character faces the static-but-mobile ghosts of murder-cults and witch hunts glitching their way towards us through our patchy simulacra of these impossibly dark caves.

[Right] An example of Seurat's pointillism. The principle involves suggesting form by building up contrasting dots of colour - a model of how the eye perceives rather than how the world is.

Scanner Sombre engages a long history of recording technology and the dreams and nightmares surrounding its development. When we enter a room it gives up its dark secrets at a sedate and beautiful pace, like a post-impressionist painting - and indeed Divisionists/Pointilists like Seurat were obsessed with time, attention (our ability to focus on and perceive the world) and the revelations of new technology (Jonathan Crary, 2000). In the 1880s, an age of new kinds of media and recording devices (from film to the phonograph), Pointilist painters and society at large were concerned by an apparent splintering of the senses into discrete quantitative registers. Once we could record sound separate from images, what did this do to the unitary identity of the subject? When a photograph doesn't age as we do, does this give us immortality, or foreshadow our death? And how should the subject negotiate a world of distractions, reflections and new artefacts - from disembodied voices to perpetually fixed images, modern recording technology seems to fragment us. Perhaps, as many thought in the 19th-Century, we might be able to find the scanning technology to record the dead, and preserve them as immortal ghosts (Friedrich Kittler, 1999). Here in Scanner Sombre, the closer precedents are data mining, LIDAR scanning of cities, and the ghosts of Google street view.

“Once we could record sound separate from images, what did this do to the unitary identity of the subject? When a photograph doesn’t age as we do, does this give us immortality, or foreshadow our death?”

Street view capturing death?

Online we can find odd archives, slivers of persons preserved by a google car - blurred portraits, absurd freeze-frames, even the repeated form of an old man slowly shuffling down a street. These uncanny remainders haunt our generation, and various post-digital artists have dedicated themselves to a digital archaeology of these digitised urban spaces, and these reified images of ourselves caught unawares and out-of-time. These technologies, which try to map a dynamic and 4D world, are fundamentally alien to us - so much so that signs of human presence can be disconcerting and uncanny. Human representations sit uncomfortably in virtual worlds. James Bridle, a leading post-digital theorist, draws interesting parallels between this and Kittler's work on the late 19th-Century, where he writes about this phenomenon in the context of 3D rendered architecture. Stock photographs of people at leisure are used to populate speculative models of future buildings - he calls these 'render ghosts' - but they sit oddly between the virtual and the real. Something is missing, and that something involves 'time'.

Render ghosts about to walk into the real world.

Aside from the realtime first-person perspective the only other frame the player can experience Scanner Sombre's game space through is a 3D map. From start to finish we build up a picture of the cave system, rendered as a 3D point cloud - caverns and tunnels fading in and out of clarity according to the assiduousness with which we scanned them. Yet this map is forever incomplete - these are dots, surfaces touched on with a comb that can never be fine enough to fully model a topology. There are gaps where ceilings are so far away that our spray of laser-light diffuses, or where there are lakes that resist recording. This is a cumulative, patchy and static map, close to the way a plant might perceive the world by growing through it - it is intimate and incomplete - and is as reflective of our own first-person archaeological journey as it is the ruins and remains of this once inhabited space.

Some archaeological geophysics

The ghostly default T-pose behind the point cloud?

“Where we began as cartographers and digital archaeologists, we end up as an artefact ourselves.”

As we approach the mouth of the cave system, our world-view becomes further confused, as ruins give way to dioramas. Everything we've touched has been a sliver of historical time working closer and closer to the present day, and ending with a museum of the mining industry we previously caught a haunting glimpse of. Where we began as cartographers and digital archaeologists, we end up as an artefact ourselves. As we leave the cave, there is no sunlight to light our way. This is no version of Plato's cave - there is no beautiful truth behind our pale scans. Instead we find a family in mourning - a family mourning 'us'. The player now realises, as the truth dawns on their character, that they are already dead, lost to the caves, and doomed to cyclically repeat this expedition through the deep time of the earth. And back we fly in the final cinematic, through the map we've made, down deep into the earth and back to where we began - the cavernous walls wiped clean, and ready to be scanned again.

What we experience in this game might be described as a world without a fourth dimension. By playing with notions of archaeology and cartography, Scanner Sombre makes claims about the ghostly nature of our post-digital world and our tenuous grip on 'time' as unreliable observers. It makes us dwell on imperfection and reflect on space and time in radically unique ways. There is a flat ontology in this dark world, and the player learns they are as much an artefact as the world they excavate.

Dr Merlin Seller

![[Right] An example of Seurat's pointillism. The principle involves suggesting form by building up contrasting dots of colour - a model of how the eye perceives rather than how the world is.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/579b06c244024383dcba1164/1498038713596-XZ41OFXXE1DALHE893AU/image-asset.jpeg)